A Name Worth Fighting For

How My Principal Helped Me Leave the Past Behind

This is an old story that has aged well, I think.

In the 80s, before I ever got to high school, the high school principal, Mr. Raber, rode his bike past my house on Crestview Drive, in Elyria, Ohio. It was a classic bike—something old, with a bell. Mr. Raber was a big man. Tall and solid, with gobs of hair. He sat up straight as a board on that bike. His handlebars demanded it.

One evening while off for summer break, he made his daily trek through our subdivision. As he passed by, a neighbor said, “He sure has lost a lot of weight,” and every night after, as he breezed by my house, I stood at the curb, inspecting his waistline.

By the end of the summer, the change was obvious. This is the image that came with me to high school. Not just a principal, but a man who pedaled past my house—a person with a routine, with sweat and willpower. In a strange way, it humanized him.

Eventually I became friends with his daughter, Monica. I knew her from elementary school, where she’d won our talent show playing Clementi on the piano. In fifth grade I’d just learned about Roberto Clemente in social studies and briefly wondered if a famous right fielder had a side hustle composing sonatas. How had my textbook missed this important detail?

In high school, you could usually find Mr. Raber outside the main office chatting with teachers and staff. He wasn’t the spotlight type. If he had a leadership style, I couldn’t name it. Our assistant principal, Mr. Solet, handled most of the visible discipline and handbook stuff. I smoked a little weed and skipped my share of classes, yet somehow stayed off Solet’s radar.

Monica was tall like her dad, quick to laugh, and bright. Being friends with the principal’s daughter should have felt weird, and maybe it did a little, but whatever weirdness there was didn’t seem to touch her, something I admired, even at that age.

In Spanish class, Monica and our friend Amy helped me conjugate verbs and taught me the difference between a hand (mano) and a monkey (mono). Spanish came easy for them—school did, actually—whereas I needed the help. Things were dark and complicated at home, which had an impact. I wasn’t a good student, but eventually, with the help of others, I was able to graduate on time, even if only with a 1.9 GPA.

Behind the scenes, my life was a made-for-TV movie, still waiting to turn inspirational. In time, after therapy, hard work, and healing, things changed. But in those days it was just survival. Trying to keep my head above water while pretending not to drown.

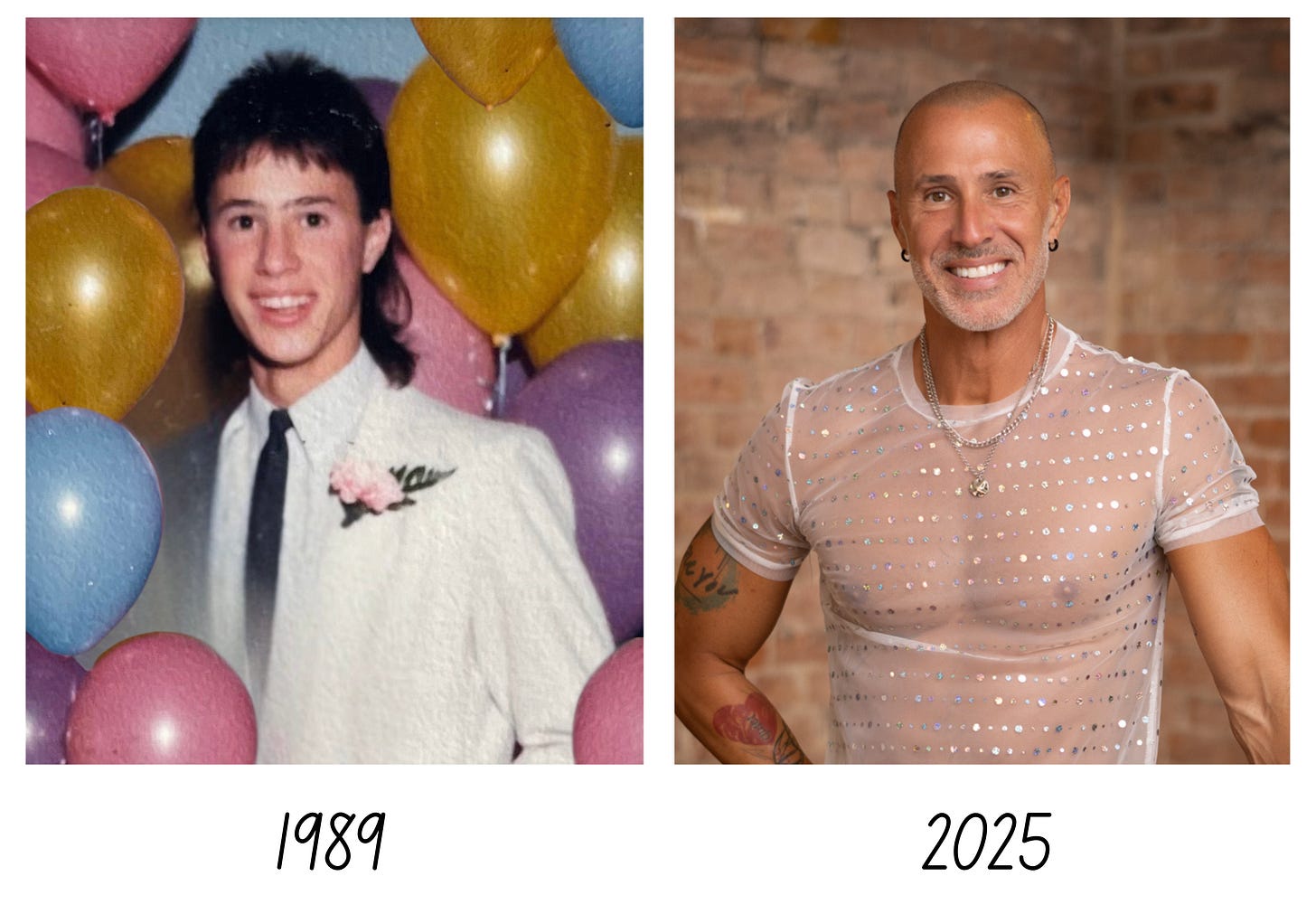

I remember the boy I was. Apart from the chaos, he had a desire to dress creatively, and put gold mousse in his hair. I have his face memorized. I remember his love for music, and his fierce desire to be good. He wanted to fix the people he loved, even when he couldn’t fix himself.

Back then my last name was Petrino. Not many people know that about me. The name belonged to my stepfather, who adopted me and my siblings when I was three. I’ve often called him the stepdad from Hell, and I don’t say it for effect. We didn’t know who he was at first, but little by little we learned. The imbalance, the fury, the fists, the control. And finally, the deviance. I lived in fear as a child. For years, as an adult, I’d often catch myself moving on tiptoe through my own house—a leftover skill from living with an abuser.

From the outside, music made me look confident. I got lead roles in musicals, won vocal competitions, and, even as a closeted queer kid, managed to date. Behind the scenes, I was an abused child—full stop. That’s all it takes to make living honestly your greatest fear. Every single day I was anxious that someone would discover who I really was. If they did, they would know I was bad, when all I ever wanted was to be good.

What happened next still surprises me. It took strength I wasn’t sure I had and a sense of self I was just beginning to claim.

And it required Mr. Raber.

In November of senior year, I turned eighteen. By then the stepdad from Hell was gone. When my mom discovered the scope of what he’d done, she divorced him. Months earlier, before my birthday, I started looking into changing my last name. I wanted to be Matt Bays again, my biological name. More than that, I wanted his name as far from me as possible.

The summer before senior year, my mom and her new husband moved to Spring Hill, Tennessee, where he’d taken a job at Saturn, the new General Motors division. I stayed in Elyria to graduate with my class. The name change would be my first solo project as an adult. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I was committed to get the damn thing done.

From the start, the courthouse was cold. Clerks and admin staff seemed irritated I was there. No smiles. No eye contact. No curiosity about why a high school kid without adult supervision might want a new name. I felt like a bother and could feel the boy within tiptoeing, while holding tight to a very old message:

Be small. Be quiet. Be unseen.

The world wasn’t a safe place for kids like me—troubled, bad student. And with no adult to vouch for me, I was on my own.

But I kept going.

I read forms I didn’t understand and filled out every line. I went back when I was told to, and then again. I wanted my name back. I can’t overstate how important this was for me.

With graduation looming, I fixated on the diploma. I didn’t want to cross that stage and be handed a document that would follow me from basement to basement, box to box, with the wrong name stamped across it. I wanted to open that leather folder and meet myself honestly.

When my court date finally came, I left class midday and walked to the courthouse. I sat in a large, empty room with an enormous Persian rug, imposing bookshelves, and a stately executive table. I sat alone for a moment, feeling like the child I still was. Then a man and a woman entered and took seats across from me. The man wore a half-buttoned robe. The judge, I guessed. The woman, maybe an appointed attorney, said hello, but was all business.

“Why do you want to change your name?” he asked.

“I’m eighteen,” I said. “And Bays is my biological last name.”

He looked at the document. “You’ve had this name since 1973. Why now?”

I wasn’t prepared for questions. I stumbled.

“Because it’s the name I was born with?”

I was too young to state the deeper reasons—that I didn’t intend to carry the name of an abuser. A predator. A madman.

“I’m gonna need a better reason than that,” he said, staring across the table.

Something in me steadied. There’s always been a quiet strength inside me. I learned it from my mom, who gathered courage from the shattered pieces of her own life, and glued them together with blood and tears and stubborn will. I took a breath and found my center.

“Why do I need a reason?” I asked, trying to keep my tone even. “Can’t an eighteen-year-old change their name?”

“Watch your tone, young man,” he said. “I’m trying to make sure you’re making the right decision.”

Looking back, I can see what he meant. I can also see how he could have done better.

“I would like to change my name,” I said again, and this time, told him the truth. “The stepdad who adopted me is a monster. I want nothing to do with him.”

It was that simple.

“That’s what I needed to hear,” he said. “Let’s do this!” and he began to write. “This young man is no longer Matt Petrino. He is Matt Bays.”

He handed me papers to sign, shook my hand, and sent me to file for a new birth certificate.

By the time I arrived back at school, I felt different. Older. Like faculty.

In the main office, I handed my documents to a fuzzy-haired woman and explained I’d need my diploma issued under Matt Bays.

“I’m sorry,” she said without looking up. “The diplomas for the 1989 graduates have already been ordered.”

I felt a lump in my throat. “Is there anything you can do? Petrino isn’t my name anymore. I’d like my new name on my diploma.”

“I’m afraid you’re too late,” she said coolly and handed back the paperwork. “Like I said, they’ve been ordered.”

No smile. No eye contact. No considering why a kid in high school might be changing his last name.

From across the office, I heard, “What’s going on?” Mr. Raber stepped away from the cluster of mailboxes where he’d been talking to a staff member.

“Well apparently, this young man has had his name changed,” the woman said.

He walked over and held out his hand. “Do you mind?” He took the papers from me and began to read.

She spoke again. “I’ve told him twice that the diplomas have already been ordered. There’s nothing we can do.”

I braced for the same answer from him. Embarrassment washed over me. I didn’t want to make a scene. I didn’t want to be seen.

“You changed your name?” he asked, eyes still on the page.

“Yes sir,” I said. He kept reading.

The woman watched me. She seemed busy, more than angry. With over two thousand students’ information to manage, I’m sure she had plenty of special requests. This was a bother. Just one more thing to do.

Say it, I thought. Tell him.

“I’ve had my name changed for personal reasons,” I finally said, the words coming out fast. “I’d like my diploma to have my real name on it.”

“And this is it?” he asked, pointing.

“Yes. But it’s fine. They already ordered them.”

“I like it,” he said, ignoring my words. “It’s a good name.”

He looked at the woman. She made a helpless face, as if the decision lived somewhere above her pay grade. I’d just have to live with it. Live with that name.

He looked back at the document. “Get him a new diploma,” he said quietly.

“But they’ve already been—”

“Order another one,” he said, not unkindly but firmly, as if any other answer was absurd. “His name isn’t Matt Petrino. It’s Matt Bays. Order the boy a new diploma.”

“I’ll see if it’s possible,” she said, writing a note in the margin of her giant desk calendar.

He handed me the papers and started for his office. “Make sure it happens,” he called over his shoulder.

“I’ll see what I can do,” she murmured. “But it’s not going to be easy,” she said, glancing in my direction.

But then, neither was getting it changed.

There are teachers and principals who touch our lives in ways we don’t fully understand until later. By the time we’re old enough to feel the weight of those moments—to see an abused boy finally get a win—they’re often gone. If Mr. Raber were still here, I’d tell him this:

When I found the courage to stand up for myself, you stood up for me, too. Thank you. You treated me as if I mattered. You treated me with respect. Thank you. You didn’t need the backstory. You read what was in front of you, and you chose right over convenient. Thank you. I haven’t forgotten. I won’t forget.

I can’t say Mr. Raber changed my life. I can say he played a beautiful part in changing my name. And that changed my life.

A few weeks later, at graduation, I opened the diploma and there it was.

Matt Bays.

I ran a finger over the letters. It was shorter. Truer. Mine.

When it came time to throw caps into the air, I didn’t. I just kept looking at my name, the one that belonged to me. I was no longer Matt Petrino. I was Matt Bays.

From the day the judge signed the document until the moment I opened that folder, I hadn’t told a soul. Not my friends. Not my mom. No one. The only people who knew were me and Mr. Raber.

After the ceremony he milled around like principals do, shaking hands, looking like the man on the bicycle, a regular guy who understood right from wrong … and that sometimes, a name is worth fighting for.

Oh, Matt. This is so lovely. 💙

So good, Matt. This little sentence was really powerful for me. I hid behind this, too.

Be small. Be quiet. Be unseen.

Thanks for writing this!