Styrofoam

The strange beauty of goodbye

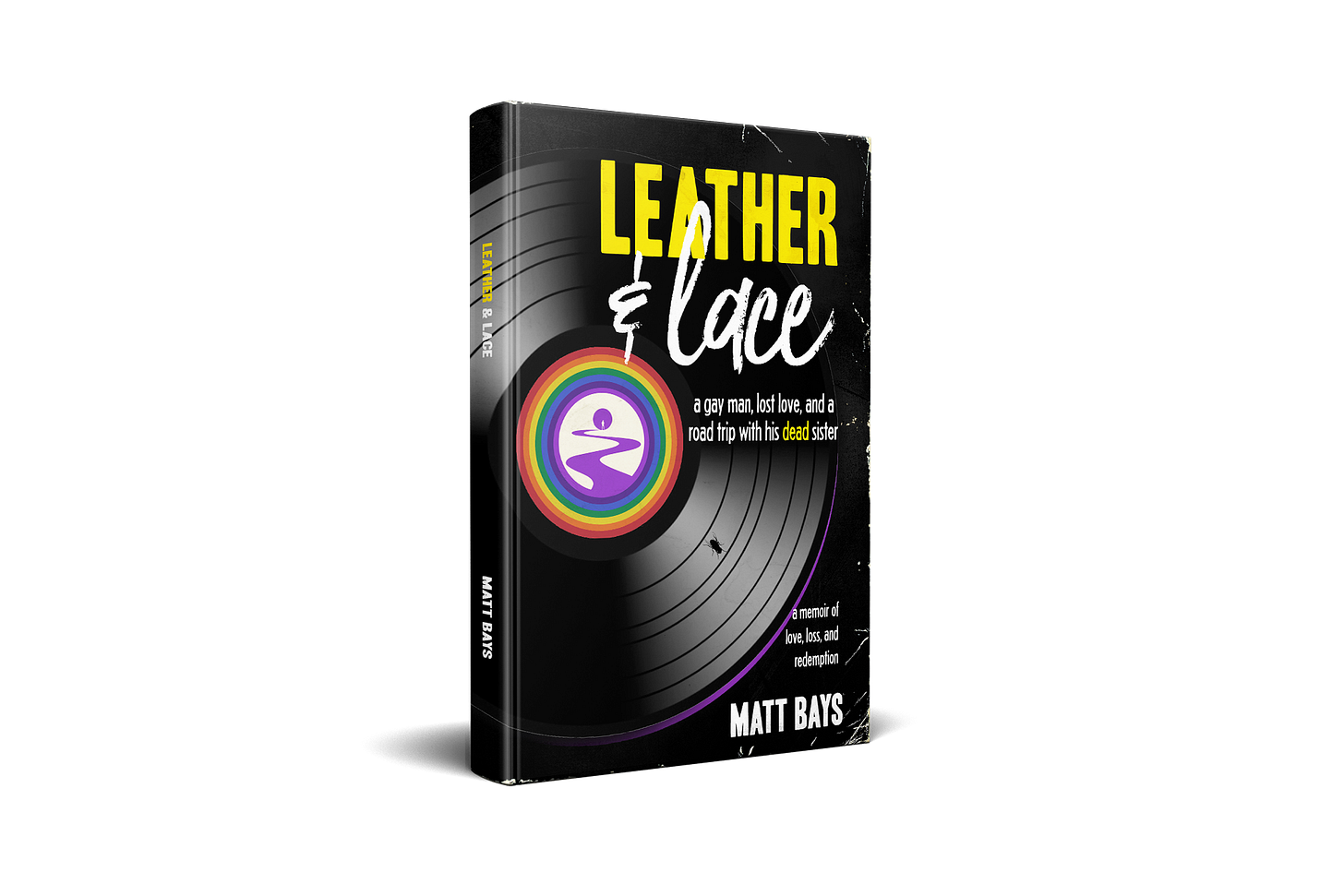

*Tomorrow marks the eve of my sister Trina’s passing—Halloween. It’s strange how the air still changes around this time, how memory has its own weather. I wanted to share an excerpt from this chapter, “Styrofoam,” from my memoir Leather & Lace: A Gay Man, Lost Love, and a Road Trip With His Dead Sister. It’s about love, loss, and the quiet ways we are shaped by both. In it, I tried to capture one of the hardest and holiest moments of my life. The morning we said goodbye.

The morning she died, we had a brief meeting with a nurse in the lobby of the hospice unit. When I left Trina’s room at 8 am, she was still breathing. Still there.

Several days before, we had gone to Target, where she loaded half the store into the basket of her scooter. “Baby’s first time on a scooter,” she said gleefully, once I was able to convince her to get on the damn thing.

“I’m not riding that,” she said.

“I would ride this thing all day if I could. This is your chance,” I told her. “Do it, Wee. Just go for it.”

Wee. It was what my brother Tim had called her when he couldn’t say “Trina.” And all these years later, it had stuck.

“I’m gonna look like a sickie, and I don’t like that,” she told me. But she was unstable on her feet, which had me worried… so I decided to go with a more direct approach.

“You have cancer, so sit your ass down.” She rolled her eyes and climbed on the scooter.

“I don’t even need this thing,” she mumbled. “So stupid.”

But she took to it quickly, riding aisle to aisle, whizzing around corners and nearly mowing people down. “It’s fast!” she said, laughing. “Why haven’t I done this before?”

At one point, I lost her. Peering over racks of clothes, I worried that something might have happened when a rack of clothes mysteriously flew across an aisle—an act of telekinesis. Trina’s scooter shot out from behind it as she shouted, “Sorry! Sorry! Baby’s first scooter ride!” I have this image imprinted in my mind—that giant grin—her enormous laugh I’ve heard a million times. I am still so proud of her.

The halls of the hospice unit were sterile that morning. They reeked of hopelessness. This is where people came to die.

My mom, Trina’s husband Chuck, and I stood together in the waiting room. Chuck looked tired around the eyes. My mom looked tired around the soul. “How long will she be like this?” I asked the hospice nurse.

“At this point, you can never really tell,” she told us. “But she isn’t in any pain. She is resting peacefully.”

While Chuck left to check on Trina, mom and I sat together near a row of windows that flanked the waiting room. Filtered light poured in through the large, inflexible rectangles. It was fall and seemed as if the leaves were having a contest, each attempting to outdo the other. For almost everyone I knew, it was going to be a beautiful day.

Just one day earlier, while shifting Trina in her bed, her body collapsed against mine. It had been twenty-four hours since she had been coherent—her mind was gone completely. Seeing her that way was hardly bearable. We had pulled her into a sitting position, and while slumped against my side, I felt three tiny kisses on my arm. That’s when I knew she was still in there—when she knew I hadn’t left her side.

Several minutes passed and Chuck reappeared in the hallway. He stood alone just outside Trina’s room, a glass partition between us. He just stood there.

Words passed over my mother’s lips. I had heard her voice sound this grave only one other time in my life; when my brother died. Hearing it like this again took the air out of my spirit.

“She’s gone,” she whispered under her breath. I couldn’t form a thought in my head. I didn’t make a sound. “She’s gone,” she said again, like a death toll. She wasn’t talking to me. She wasn’t talking to anyone, except maybe to herself—to the young woman who had given birth to this amazing creature fifty-two years earlier.

I don’t understand loss. I know that it’s a part of life; I just don’t know why. And I don’t understand how it is that we get better, though not all the way. Love is born within us and then recklessly ripped out. CS Lewis spoke in universities, telling his students that pain was a megaphone to rouse a deaf world. But death isn’t a megaphone. It’s a cruel lullaby—a lament that doesn’t rouse or revive. It lulls a part of us to sleep or twists our arms into acceptance. And the world is such an unkind place. Maybe God is too. Or is it just me?

Several days earlier, Trina called me into her bedroom. Her unwillingness to make preparations had us all believing she was in denial of what was happening. We wondered if she even understood that she was dying.

“Sit down,” she told me. And I did. Her face was serious. Determined. Unafraid.

“I want Steve Carney to do the service,” she said. “And I want you to plan the music. Just make it nice and do your thing.” I watched her. She was calmer than I’d seen her in a long time. This was not a woman in denial. This was a warrior who had chosen to live her final days rather than plan for her death. How could I have underestimated her?

“Come here,” she told me, and I followed her into the closet. “This is the dress I want to be buried in.” It was the one she’d worn at her wedding—a silver dress with puffy sleeves and Swarovski crystals surrounding the neckline. “And I don’t want to wear a wig,” she said. “I don’t want to pretend I’m something I’m not. (I took a deep breath when she said this.) And besides, I think I look good like this.”

I thought back to all the times she had gained weight and would enthusiastically tell me, “I mean, yes, I’ve gained weight. But I look really cute chubby!” I smiled and held back my tears. I knew that I knew that I knew… she wasn’t replaceable. Accepting this truth would be a more difficult challenge.

“No wig,” I said. “Good. I think you look perfect exactly as you are.” I tried to stop the tears again but was feeling overwhelmed—so grateful and so overwhelmed.

“It’s going to be okay,” she said. “You are going to be just fine. I love you so much, Matt.” She grabbed ahold of me and I buried my face in her neck. How would I ever let her go? How would I ever be okay again? She was the one dying, yet she cared for me—comforted me, as she always had. With one hand rubbing my back and the other wrapped around my neck, I realized she was saying goodbye.

She held on to me in that closet—in her closet. What I couldn’t have known at the time was that in just one year, I’d need her to hold me again as I came out of mine. She was everything to me.

Show me how to live. Show me how to love. Show me how to die. Just show me, Trina. Show me everything.

An hour after she passed, her son and two daughters came to the hospice unit and said their goodbyes. As Trina laid there, her mouth still shining with lip gloss, we all sat around her one last time.

It was a Monday. It was Halloween.

When we arrived home, the twin red maples in her front yard were on fire, as bright as I’d ever seen them. The world around us was oblivious, insisting that life goes on. Children were riding their bikes. Imitation spider webs were spread over rounded shrubs. Garage doors were rising and falling no more swiftly than my sister’s breathing one night earlier.

For the next two days, we lived underwater—an emotional slack tide that slowed the whirring waters to a complete standstill. Nothing was coming in. Nothing was going out. We laid in Trina’s bed as if we’d been buried in sand. We sniffed at her clothes as if we were breathing in the ocean.

“Come here,” my niece Alyssa said, walking me into the same closet Trina had held me in days earlier. “Smell,” she said, holding up her momma’s robe. For the next fifteen minutes, we traded off, smelling Trina’s robe, hoping we’d never forget her. How had she lingered there? And how long would it last?

In grief, life either has too much meaning or none at all.

“Absolutely, you can do her makeup,” the funeral director told us. Jessica and Alyssa wanted their mom to look like their mom at the visitation. Their brother Matthew likely didn’t care but stood in solidarity with them.

“We just want to make sure she looks like herself,” Jessica said.

“It’s no problem at all. Give us a day to get her ready, and you can come by tomorrow.”

The next morning, the four of us loaded into the car and headed off to make Trina beautiful. She deserved this.

In college, I had worked at a funeral home. Apart from one old lady rolling off a gurney and faceplanting on the pavement while being loaded into a hearse, all had gone well... apart from that. Fixing her teeth was the most challenging part. But in the end, her family decided to have her cremated, which was a relief. Needless to say, I was used to the oddities that often accompany life in the funeral home business. So I was prepared.

“Your mom is going to be behind this door,” the funeral director told us. “I want you to ready yourself. She is dressed, but you’ll see Styrofoam blocks in her hands. Please know that these will be removed before calling hours this evening.”

“What’s with the Styrofoam?” I asked. In my limited expertise, I’d never come across this sort of thing.

“They help to form her hands, giving them the right shape for the services.” I nodded.

Sometimes the most random memories come into our minds. That word: “Form.” A bible verse containing the word “form” had profoundly interested me in my thirties.

“But this is what the Lord says—’he who created you, Jacob, he who formed you, Israel: Do not fear, for I have redeemed you; I have summoned you by name; you are mine.’”

The meaning of Jacob’s name was “deceiver,” while the meaning of the name, Israel, is “triumphant in battle.” Apparently, God had created a liar and then formed that liar into a fighter. I knew something about this. I had lived dishonestly my whole life. I needed to be formed. I had never been the right shape.

As the funeral director opened the door, there was a deep, communal breath between us. We stepped into a narrow room, and there she was, laid out on a steel table. The Styrofoam blocks were snuggled in her grip like a stuffed animal. It was the most utilitarian display; steel table, Styrofoam blocks, and harsh lighting.

Trina’s makeup bag was slung over Alyssa’s shoulder. “There’s more makeup here if you need,” the funeral director told us. “I’m going to give you some privacy now. Just come by my office when you’re finished.”

I couldn’t believe she was allowing us to care for Trina this way. It seemed the kindest thing. When death is your business, it’s not uncommon to get a little numb to it all. But she hadn’t. This was about us. It was for us. She hadn’t lost her empathy, and I was grateful.

The door closed behind us and we stood in silence before our mother—our sister. None of us knew what to say, maybe because Trina had always effortlessly made conversation, creating it out of thin air when necessary. I felt compelled to speak first—to relieve this awful scene before her children. To be a good uncle. To provide a bit of wisdom in a moment likely to be the worst time of their lives. But I couldn’t find the words. She was their mother, but she was my sister too.

Finally, it was Trina’s youngest—her son Matthew, who broke the silence. Out of the mouths of babes, we’ve been told… or something like that. Turns out, we didn’t need my words at all. We needed Matthew’s dry sense of humor, which couldn’t have come at a better time.

“She always loved those Styrofoam blocks,” he said, as if they were a long-lost treasure. As if we’d gone digging through Trina’s sentimental things and placed them gently in her hands so she might take them into eternity. Right then and there, this little narrow room erupted with a big, expansive laughter. It was just what we needed. Grief was shuffled to the back of our brains and we began the community event of making this woman look exactly like herself.

“Laughs are exactly as honorable as tears… I myself prefer to laugh, since there is less cleaning up to do afterward.” -Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

We had survived this terrible moment together, and Trina looked gorgeous at her visitation. From across the funeral parlor, it looked as if she were only sleeping, hands neatly formed into just the right shape. I made my way through the crowd where family and friends had shown up to say goodbye. Family and friends—this can often present its own set of problems. But wherever there were hard feelings, they disappeared completely, which was no surprise.

Trina had always been good at forgiveness.

Show me how to live.

And then there were the down-and-outers. They had come to mourn a woman who’d only ever seen them as God did. She spent her days working with people who struggled to make life work—with those who had lived in the margins, trying to survive whatever had happened in their troubled lives. And I was a down-and-outer too. A liar. A closeted gay man who had been scared to death ever since I could remember. But I always had my sister, and they did too. And she rejoiced over every last one of us.

Show me how to love.

I stood before her casket, marveling at how beautifully shaped her hands were. I wondered if what was hardened and immovable in my own life might ever become something else. Created as one thing. Formed into another.

Show me everything. Just show me, Trina.

*Thank you for reading Styrofoam. It’s a small piece of Leather and Lace, a story about losing and finding—my sister, and myself. If Trina’s story moves you, I hope you’ll spend more time with the book. It’s available on Amazon here: 👉 Leather and Lace on Amazon

And if you do read it, tell someone about it. Stories, like love, are meant to be shared.

What a lovely, touching story, in these days of so much angst from outside, about the simple humanity of our love for our loved ones, which comes from inside ourselves. Thank you, Matt.

This had me mesmerized from the first sentence. Your words melted me in all the feelings. What a beautiful brother you are.