Time is linear, though never in the heart.

She died on Halloween morning, which is as good a day to die as any, I suppose. I sat up with her the night before and then slept across the hospice room on a thin mattress. ‘80s music kept us company. "The Rose" by Bette Midler, "Always Something There to Remind Me," and "Don't Stop Believing," especially, are the ones I most remember—Steve Perry's soulful vocals asking me to hold on to that feeling.

In just a few hours, neighbors would gather on driveways and around fire pits, while ghosts, goblins, and Katy Perry look-alikes snatched handfuls of candy from big plastic bowls.

Trina did not go gently into that good night. Hours before, she had repeatedly pushed herself out of the bed while we did our best to coax her back under the sheets. She had no reason to get up other than to establish the sense of control she had always known as a firstborn. Her broken body kept at it, heaving itself forward as if she'd head to the kitchen to make herself a cup of coffee or fill a bowl with mom's potato salad. But hospice had come to take her.

These were her last moments, and we could feel it in the air. Something was coming for her. I didn't know it at the time, but something was coming for me too.

"Wanna go with me," she asked? It wasn't a question that needed an answer. I dropped my paintbrush in the cloudy water glass and grabbed my shoes. There was something soothing about a good paint by number. Add the appropriate colors to the designated areas, and by the time you were done, jigsaw puzzle-like plots turned themselves into barns, split rail fences, and a little black pony running for the edge of the canvas. Being part of the transformation of something empty and bleak into what the artist had always intended was a privilege. It was a kindness.

I slipped on my Super Friends tennis shoes, and together my sister and I headed out for an eight-pack of Pepsi-Cola. This is where we felt free.

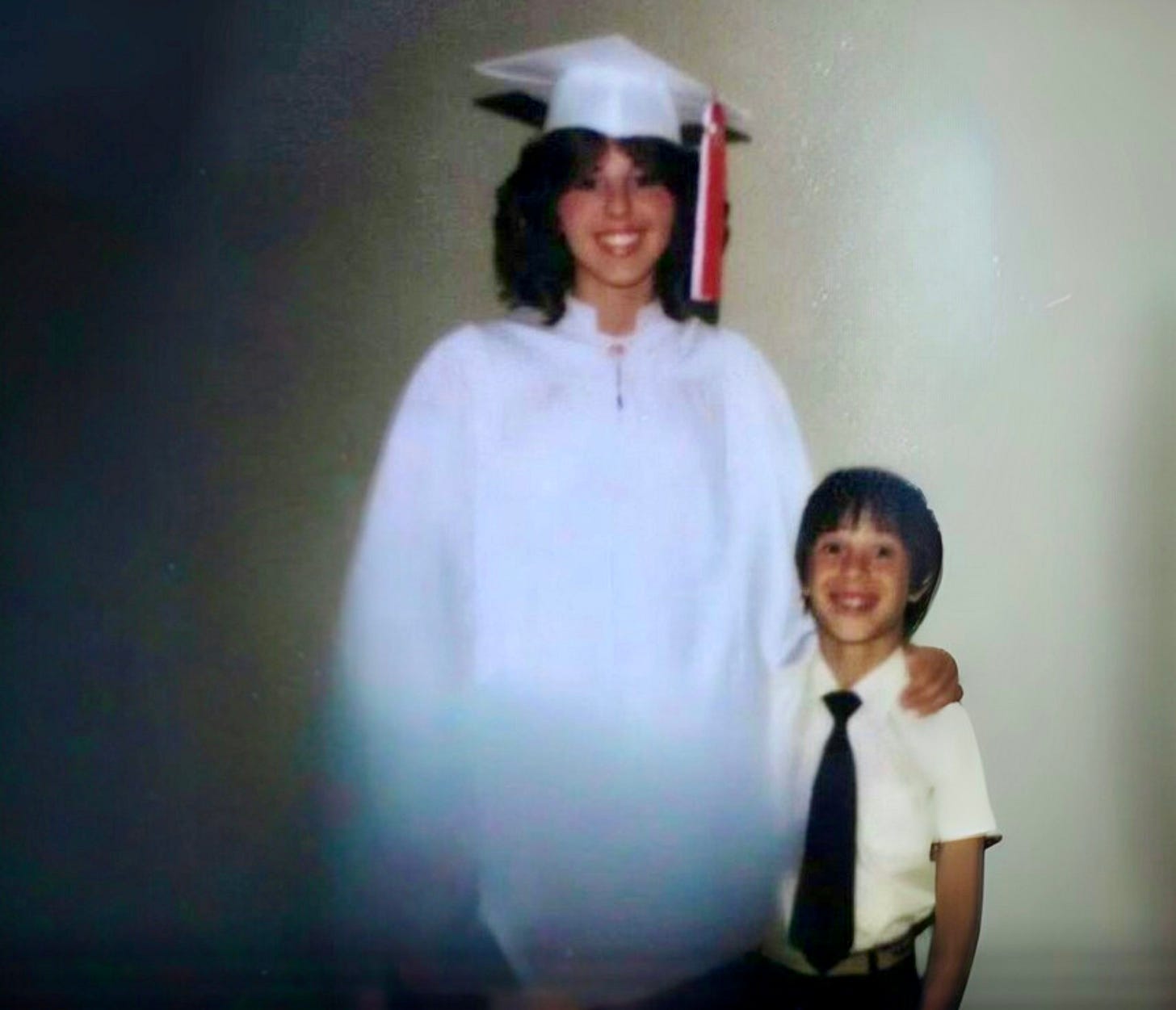

Windows down, wind in our hair, punch the fingerprint-covered square chrome buttons on the radio, and sing our guts out. She was six and a half years older than me—a big sister and mother figure all wrapped in one. And she took me everywhere with her. To say I looked up to her is a massive underestimation of my affections. To me, Trina was everything. She had her driver's license, could do a near-perfect jack-knife at North Rec pool, and used hot rollers to turn herself into Kelly Garrett from Charlie's Angels. She was a star; I was sure of it. I was just ten years old, but as far as I could tell, she was the most famous girl in our hometown of Elyria, Ohio.

“You in the moonlight, with your sleepy eyes, could you ever love a man like me?”

Don Henley’s voice blared into the car—it was exactly what I wanted to sound like when I grew up. Trina covered Stevie Nicks’ part from the driver’s seat of her 1977 black Monza. You aren’t aware of your need for each other at that age. But in the heart of a chaotic childhood, a mystical bond had formed between us without our even knowing it.

“Lovers forever, face to face, my city, your mountain…stay with me, stay.”

This was our escape. From what? From the abuse. From our lives. And from what I would be on the verge of discovering about myself in another thirty years or so. We needed this. We needed each other. Stay with me, sister. Stay.

One week before Trina passed, we brought her home from the hospital. Calcium had built up in her system and was being released into her bloodstream at toxic levels. Only two medications were available as treatment, though neither would be a long-term solution. It was the beginning of the end.

While in the hospital, she lost her mind. We hadn’t seen her this way—paranoid, restless, angry, and belligerent. Her fun-loving personality had been replaced with suspicion. Nurses were the enemy, and if she felt we were plotting along with them, then we were too. It was hard to see her this way, though not overwhelming. She was my sister, and we’d get through it.

After several days, they released her from care. She was sent home while hospice was sent in. The minute we left the hospital, she was herself entirely. The fog surrounding her within the sterile walls of her third-story hospital room was replaced with a sound mind. I told her about accusing the nurses of putting ink in her IV and believing that several of us were in cahoots with them. She laughed. She had always been the laughing kind, and I relished each one of them because I didn't know how long we had.

On the way to her house, we stopped at a local Popeye’s. For years, I had bragged about their chicken, their biscuits, their incomparable Cajun gravy. She sat across from me in our booth, oohing and aahing over every bite. I carry a picture of her from that day in my car.

We arrived home and got her set up on the couch. Her daughter grabbed the TV remote and started scrolling through channels.

"What do you want to watch?" Alyssa asked.

“Gladiator.”

“Seriously? You want to watch Gladiator?” she asked, clarifying this random selection.

“Yeah,” Trina said, “I wanna watch someone get their ass kicked, besides me.”

A little later, just before Commodus is finally killed by Maximus, I heard her whisper, “Ooo…I love when Joaquin Phoenix gets it!” And there she was. There was my sister.

It was seven more days before she’d be gone. Five of them, she was with us. Still loving. Still painting her nails. Still Trina. But the last two, she was nowhere to be found. She had disappeared on us completely.

After her graveside service, everyone who had gathered on the cemetery's lawn headed for their cars, including me. Just before getting in mine, I turned back her way. I wasn’t finished. Something had been left undone. I hadn’t said all I needed to say, so I shut the van door and made my way through the wet grass and over to where she was.

Tears streamed down my face as I stood before her grave. Yellow roses were placed on top of her casket, which were her favorite. Inside, she lay with a shaven head because she had decided against wearing a wig. I thought it was the bravest decision. I was so proud of her.

“I want to be myself,” she had told us. “I don’t want to pretend.” I was in awe of her courage—of her moxie to say to all of us…

I have cancer…let’s not dress this up…let’s not pretend this hasn’t been hard. And let’s not for a second pretend that I’m not beautiful this way.

She was herself, always. I wasn’t sure I had ever been.

I had guarded the truth of who I was for nearly three decades, protecting myself and others from what I thought would be too much...for all of us. But the hiding, the lying, the pretending had been only too much for me. Had taken its toll. And in this mask-wearing world of pretend, I had become hardened.

Like leather.

I stood before her casket, a ring of flowers creating a safe hoop around us. I couldn’t let her float away without telling the truth to my greatest friend. I had always known Trina wouldn’t be disappointed, so I was never hiding from her. I was hiding from myself. I was the disappointed one.

One hour earlier, during the funeral service, I sang the words, “Let me love you until you learn to love yourself.” I told everyone in attendance it was a message from Trina to them. It would be several years before discovering it had been a message from her to me—a sweet soliloquy of permission to be, to live, to love.

Tall, thin pine trees stood bearing witness as I offered what felt like my last rites. “I should already have told you this…” I said, standing before her, “even though I’m sure you already know. But I need to say it out loud. And I want you to be the first one I say it to; the first person I tell.” I drew a deep breath and closed my eyes. Scenes from junior high, high school, and college floated through my brain. I saw a young boy who had tried hard to be someone he could never be. I saw myself in the care of my perfect sister, dancing to the Bee Gees and watching her do her makeup. I knew what I knew. I suppose I always had. And then, I found the strength to say the words I had never before spoken.

“I think I’m gay, Trina. I’m pretty sure that I am. And I don’t know what to do.”

With that, I wiped my tears, told her I was sorry to leave her there, and headed back to my van.

She’s been gone nearly four years now. A lot has happened since. A divorce. A coming out. The spurning by a spiritual community. New friends.

And my first true love, Luke.

I had loved before, but never as my true self. Living honestly offered a different kind of love. There were fireworks and passion. Tears while making love. And during this time of transition, a settling occurred like I had never experienced. Peace came while fear was driven out. It was something I didn’t expect. Something I didn’t know was a thing.

I opened my heart all the way up and had the time of my life. I fully expected that this new relationship would last forever. But love makes promises it can’t always keep. And a painful breakup left me shattered and searching. For what? I didn’t know. Maybe for a fling. Or another great love.

Or for myself.

Who was I at forty-nine years old? A single gay man who'd left a twenty-three-year heterosexual marriage and promptly entered into his first gay relationship. I hadn’t truly experienced the ups and downs of dating, or of searching for a companion, or knowing who the hell I was. This was the first time in my life that I had actually been alone. I was navigating a world that was foreign to me—one I didn’t understand. And I longed for my sister’s hand of guidance. I needed her.

“Get out there,” I was told. “This is your big chance.” If any of this was true, it didn’t feel true. Nothing felt right to me. A familiar fear had taken up residence, stocking every shelf in my heart with self-doubt.

The day Trina’s cancer returned, she repeatedly called my cell. I left a meeting at work to take her third call. As she spoke, she revealed the news of how it had spread through her body like wildfire. I walked to the parking lot and got inside my fifteen-year-old Cadillac Catera. I wasn’t going anywhere, except that my body was pushing itself forward.

When our conversation was over, I put my head in my hands and cried harder than I had in a decade. I didn’t know when, but I understood that Trina would be leaving me. I was more afraid than I had ever been in my life.

I’ve always believed that true fear (the penetrating kind) is largely connected to life-altering tragedies and the change that nearly always accompanies them. Cancer changes things. So does divorce. Addiction. Death. But maybe the real fear—the actual fear—is that we won’t change. That we can’t.

It seems I’ve forever been waiting on someone to set me free...my sister, my first love, Luke, etc. But then that someone dies. Or you realize you can’t be with them anymore. Or they realize they can’t be with you anymore, though you've tried like hell to hold it together. And in these losses, we face the possibility that we are not nearly as connected to them as we thought. And this reality scares the shit out of us because we've been living all this time as if what made us who we are is them, not us.

When Trina died, I became an orphan-sibling because no one else knew our stories. No one else had lived them with me. And now, three and a half years later, I was losing the man of my dreams—the one whose presence in my life had turned me into someone better, someone honest, someone loved. I couldn’t bear it. I felt as if I’d always be sitting alone in that fucking Cadillac Catera, head pressed against the steering wheel, crying the kind of tears that wouldn’t change a goddamned thing.

I couldn’t do this. I needed to get out of here and find myself...for the first time. Or maybe the last time. I had spent an entire childhood feeling “other.” Wondering who I was and how to lose that feeling. My sister did what a sixteen-year-old could to help make sense of things for me. Her enormous laugh had always been a buffer to the pain that came near me.

“I’d rather come from a broken home than live in one,” she had once said. She saw possibilities in the impossible. I wonder if she still saw them in me.

Everything about her was trimmed out with beauty and love. In fact, love was the defining decoration of her life.

Like lace.

Her light was always getting through. But then love is so damn fragile.

Standing at her grave, I said what I had to say. It was the first time she couldn't tell me what to do, though I longed to hear her voice just one more time. Leaving her behind, I assumed I had left empty-handed. What I couldn't have known was that there was a road trip on the horizon—a road trip with my dead sister. She was gone, but not altogether. Because in the heart, time is not linear. Thank God for that.

Nearly four years later, with the windows down, Trina's hot-rolled hair is billowing as she cranks up the volume knob on the push-button radio. We are going on a journey—a journey to find me. And I'm nervous as hell. There is a telling look on her face because she already knows who I am, so she hasn't a care in the world.

This nearly famous hometown Elyria girl could demolish my pain with a good road trip. And here were again—ten and sixteen in her black Monza. Free as birds and flying out into suspended time.

“I need you to love me,” I tell her. “I need you today.”

Understanding my cry for help and how deeply I still needed her—she smiles softly, turns my way, and sings…

“Give to me your leather…and take from me, my lace.”

*If you are looking for a a full-throated story of life and love, pain, and self-discovery, you’ve just read chapter one from my memoir, Leather & Lace: A Gay Man, Lost Love, and a Road Trip With His Dead Sister. It’s available on Amazon and Audible (read by me.) Purchase Her

Such a beautiful and heart full story. Thank you for sharing your sister. Thank you for sharing you.